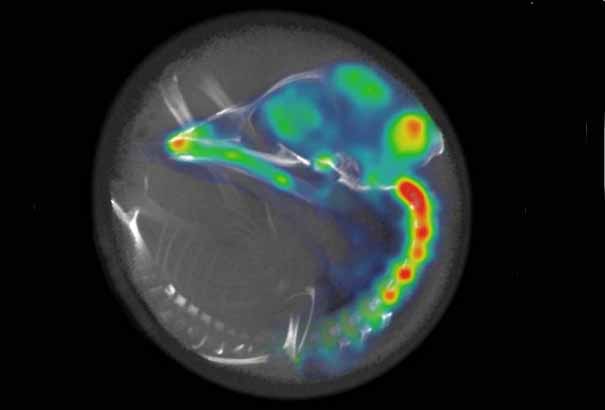

An X-ray computed-tomography image of the chicken embryo skeleton inside an egg. Image: Balaban et al. Current Biology

Your brain may already be awake before you are born.

Our brains could function in a waking-like manner well before birth, according to scientists from Spain and the US. Their findings, which were published in Current Biology, not only have implications for developing chickens and other animals, but could also affect prematurely born babies.

“We’ve found that, unlike previously thought, embryo brains are capable of ‘waking up’ prior to air-breathing and birth,” says Dr Evan Balaban from McGill University in the US. “It will be exciting to explore what this means for our understanding of brain and cognitive development, and all of the things that can go wrong with it.”

To determine when this waking state starts, the researchers woke chicken embryos inside their eggs by playing loud, meaningful sounds such as danger calls. They captured the embryos’ brain activity using molecular brain images, which can detect tiny amounts of tracer molecules and pinpoint them to a very small region of the brain.

The researchers found that the waking process for chicken embryos starts 80 per cent of the way between conception and birth, when the higher brain regions are turned on and they enter a state that resembles sleep. When they were be woken from the sleeping state by a meaningful sound the pattern and intensity of their brain activity was similar to that of an awake, post-hatching chick.

“We think it is likely that human foetuses also develop similar, integrated brain functions, including sleep-like states and the ability for waking-like brain activity before birth, although we can’t say exactly when this would start.”

Chickens are able to stand and function shortly after birth, which suggests that their brains may show these capabilities earlier than humans. However, the development schedule for many brain traits in precocial species such as chickens is not too dissimilar to that of humans and other altricial species, according to Balaban.

This change in brain activity could help clinicians and scientists examine the risks of brain, cognitive and learning disabilities for prematurely born babies. The age at which prematurely born babies can reliably survive is getting younger and paediatricians are concerned about optimal environmental conditions for assuring normal brain development outside of the womb.

“Prenatal brain stimulation/waking-like function driven by external events may be a good thing, a bad thing or an indifferent thing, and these possibilities can only be answered by future work,” Balaban says.