At was nearly two o’clock in the afternoon, the people gathered on the shore of the Gatun Lake became more and more excited. Everybody was looking at the dam, that seperated the lake and the new canal. To engineers and workers, who had worked hard for nine years, as they constructred the Panama Canal, every second seemed like an eternity. But everything went according to plan.

At 14.02 sharp, there was a huge explosion, and cascades of water rose into the air. The crowd cheered, as the roaring water flooded into the canal. The powers of nature had been tamed, and the workers had created a short cut across the American continent – from the Pacific to the Atlantic Ocean.

The explosion was a technical feat in itself. The dynamite, which blew up the dam, was ignited by remote control by President Woodrow Wilson. He pushed a button in Washington, DC more than 3,000 km away and linked the telegraph to a release mechanism at the Gatun Lake. The spark made the dynamite explode, blowing up the dam, so the water of the canal could flow freely.

The way in which this last turf was cut was intentional. The remote-controlled explosion symbolised technical innovation, human inventiveness, and spectacular physical strength – qualities, which were decisive for carrying out the world’s greatest engineering feat so far.

The French gave up

In 1881, the French were the first to try to construct a canal through Panama. The leader of the project was Ferdinand de Lesseps, an engineer, who was the man behind the construction of the Suez Canal in Egypt 12 years earlier.

Unlike the Suez Canal, which was built across a flat, dry desert, the Isthmus of Panama was hilly and marshy. After eight years, tropical diseases, flooding, and landslides had made life and the efforts so difficult that the French gave up and went home without having achieved much. 20,000 people had been killed in Panama’s hostile environment, and Ferdinand de Lesseps was ruined and declared mentally ill.

10 years passed, before anyone dared to try again. At that time, the world was changing, and the technological development sped up. Factories mushroomed in Europe and the US, as railways spread across the continents. At the same time, a new financial superpower had emerged. The huge resources and manpower of the US provided unprecedented opportunities, and the aims were high. In the opinion of President Theodore Roosevelt, nothing was impossible for the US, and he was determined to make the country the world’s leading industrial power. In order to achieve this, goods and raw materials had to be able to move freely throughout the world. A short cut from the factories of north-eastern USA to the markets on the west coast and in Asia was crucial.

Technology must spread

President Roosevelt did not worry too much about the fact that the region, which he had selected to be his short cut, belonged to Colombia. In his opinion, the US was doing the world a favour by spreading the blessings of technology and civilisation, so he had no scruples about the diplomatic tricks and military pressure he used to seize the Canal Zone, a 1,430 km2 area of Panama where the canal was to be built.

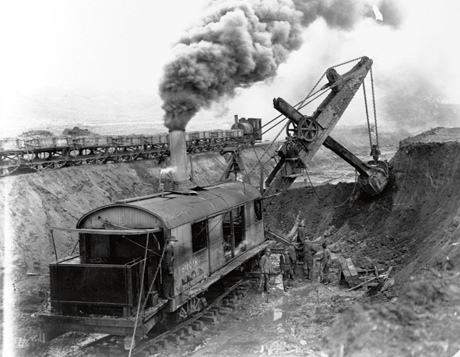

On 4 May 1904, the work began. Chief Engineer John Findley Wallace had bought giant steam shovels, 95 tonne excavators, which could remove eight tonnes of Central American soil per shovelful. After a few months of excavation, the work came to an abrupt stop. Nobody had thought about how to remove the excavated soil. Without enough railway capacity and a well-researched construction plan, the work drowned in soil. Frustrated, Wallace quit his job. Instead, Roosevelt hired John Frank Stevens, who had participated in the construction of several North American railways.

Stevens modernised the railway and made it a driving force of the project. The railway was use not just to remove the excavated soil, it was also to run close to the canal from the city of Colón by the Atlantic to Panama City by the Pacific Ocean.

The trains brought all equipment, from steam shovels to mortar and supplies, and they were higly reliable. All operations were rationalised and mechanised. To be able to extend the tracks, as the construction of the canal progressed, Stevens had a special crane made, which could lift both rails and sleepers without separating them. The crane enabled the workers to extend the railway by more than 1.5 km per day.

Mountain removed with dynamite

Stevens’ mechanisation soon paid off. In the autumn of 1906, the canal work progressed smoothly. A work force of 24,000 drilled and excavated their way across the Isthmus of Panama from morning till night in tropical heat or heavy rain.

The men removed soil, dug trenches, and cleared away trees and bushes, so steam shovels and dredgers could set to work. The most strenuous work consisted in cutting through the Culebra, a mountain range, which traversed the planned route of the canal. Using steam-drills, the workers drilled holes in the mountainsides, where they placed dynamite and blew up the rock into smaller pieces that could be removed by steam shovels.

It was hard and dangerous work, which was carried out in a country where temperatures could easily reach 48 °C. The noise of the 300 steam-drills and the 60-70 steam shovels was accompanied by the eternal hiss of the omnipresent railway engines and the roar of explosions.

The inferno was almost unbearable, but the sound, which workers feared the most, was that of the whistle. The continuous sound meant that a landslide had buried a team of workers, who were to be dug out. For most of them, it was too late, and the shadow of death always hung over the construction site. Explosion accidents took their toll, and people died so often, that engineers built a special railway to the cemetery, making it easier to bury the dead. A total of 10,000 men were killed during the entire project, or 30,000, if counting the French losses.

Tugboat tested the locks

In spite of the Culebra difficulties, the work continued at a steady pace, and around 1911, the canal started to take its final shape. The technological feat attracted the attention of the whole world, and reporters and tourists flocked to the Canal Zone. Nothing attracted more attention than the huge locks, “the grand gates of the Panama passage”, as the press put it.

Three sets of locks were to take the vessels across the Isthmus of Panama. By means of a system of valves, water was directed into the big lock chambers, and the ship was elevated. The lock chambers were the biggest ever made. The huge amounts of cement – no less than 5 million sacks and barrels – were mixed on site and poured into big vessels, which held six tonnes each. A large crane moved across the locks on cables and lifted the vessels and emptied them into the hole where the lock was to be built.

To ensure a smooth passage, all lock functions were measured and tested. And when the tugboat Gatun tested the locks on 26 September 1913, the gates opened like clockwork. Two weeks later, on 10 October, President Wilson pushed the button. The Panama Canal had become reality.