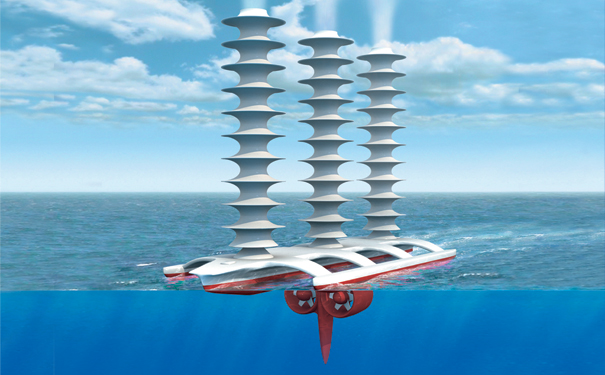

Artist's impression of the Cloud Maker. Image: J.MacNeill

In the meantime, geoengineering has been gaining ground. In 2006, Paul Crutzen, an atmospheric chemist at the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Germany and a Nobel laureate, published a scientific article in the peer-reviewed journal Climatic Change describing how we could, in principle, cool the planet by reproducing the sunlight-reflecting atmospheric conditions caused by volcanic eruptions. Last September, scientists from the UK’s Royal Society published a report on geoengineering, describing it as “potentially useful” and “probably technically feasible,” and recommended further research. Two months later, the US House of Representatives held the first in a series of hearings to help determine if geoengineering could be a tool in the fight against climate change and how much funding should be set aside for research on the strategy should it prove useful. In just four years, the idea of engineering the Earth itself to combat climate change — long considered impractical, implausible and in some cases, downright foolish by all but a handful of supporters — has managed to grab the attention of both scientists and politicians. And it isn’t letting go.

Rebooting the Earth

There are two main classes of geoengineering projects. The first, known as solar radiation management, focuses on deflecting the sun’s heat back out into space. Earth already reflects about 30 per cent of the sun’s heat and light, mostly with clouds, the oceans, snow and ice. Increasing that figure by as little as 1 per cent could help combat climate change. Proposed solar radiation management techniques range from the mundane, like painting roofs white and planting more-reflective crops, to the extreme, such as launching giant mirrors into space. Straddling the middle ground of the simple and the audacious are techniques that inject clouds with salt particles to make them whiter and more reflective.

The second main geoengineering method captures carbon dioxide before or after it is released into the atmosphere and stores it — underground, for example, or at the bottom of the ocean — reducing atmospheric CO2. Artificial trees, methods to boost populations of carbon-loving plankton and smokestack filters that catch carbon before it’s released into the atmosphere are all in the works.

But both solar radiation management and carbon mitigation come with risks. The former could cause significant changes in the Earth’s weather patterns — changes we can’t anticipate. Likewise, plans to capture and store carbon dioxide underground or in the ocean could cause seismic activity or could further stress already fragile marine ecosystems. Even geoengineers caution that their plans aren’t a cure-all. Carbon dioxide removal is a slow process, and would have to be implemented in conjunction with carbon-emission cutbacks in order to be meaningful. And although solar radiation management could cool the planet more quickly, it would have to continue indefinitely if it weren’t also coupled with emissions cutbacks. “Geoengineering buys you a 50- or 100-year window to continue working on the problem of emissions,” says Martin Bunzl, the director of the Initiative on Climate and Social Policy at Rutgers University in the US. “It isn’t a substitute for the aggressive need to limit carbon output.”